Colette Sadler originally trained in classical ballet in Glasgow and London, before joining Transitions Dance Company. Her appetite for contemporary dance whetted, she went on to work with Liz Agiss and Wayne McGregor, amongst many others, before founding her own company, Stammer ,in 2002. Having presented work at Tramway, Dance Base and as part of New Territories, her choreography is always intelligent and provocative, pushing at the boundaries of dance.

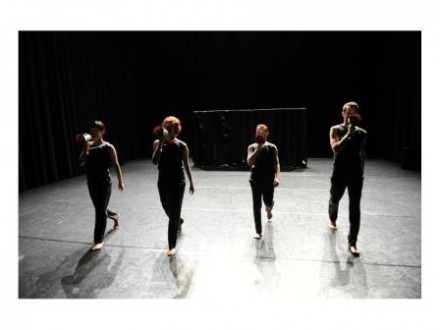

Hot from a successful run at this year’s Fringe, Musical is her latest show. There seems to be an irony in the title, since Sadler’s dance emerges from a very different tradition than musical theatre, with its jazz hands and hit songs.

“ I am deliberately provoking multiple interpretations of the word Musical,” she begins. “The show deals with a certain critique of entertainment taking references from comic burlesque and music-hall tradition.”

While neo-burlesque has been all the rage over the past decade, Sadler has mined further back in time. “My initial inspiration came from the Britannia music-hall theatre on Argyle street,” a wonderful old music hall currently being rescued by a dedicated team of volunteers, recalling an age where popular performance was something both subversive and vibrant. Further influences include “tap dance and the films of Jaques Tati and Monty Python.”

Despite the austerity and seriousness usually associated with contemporary dance, Sadler is looking for something more. “It is unusual that dance and performance are really funny, but being funny was one of the aims of this show,” she continues. “ I myself enjoy a good laugh and we had a lot of fun making Musical.”

One of the key aspects of Musical is that Sadler has worked closely with a musician to develop the piece. “I worked with Austrian composer and musician Noid on this piece and our interest was to find a place where musical composition and dance could become one and the same,” she explains. “In actual fact, the whole choreography can be read from the point of a musical score.”

Sadler’s approach is always distinctive. With her experience working across Europe, Sadler has pulled in influences from across the world, but returns to a core strategy. “All of my works are strictly choreographed, as I am not at all interested in improvisation as performance.” This does not, however, preclude a more active role for her dancers. “The performers are, however, closely involved in researching and proposing movement material. For that reason, I credit them also with the choreography.”

This is a common tactic in contemporary dance, making Sadler choreographer, artistic director and conceptualist. “My role is to propose the concept or theme of the piece,” she elaborates. “I am always responsible for orchestrating and composing the movements in time and space. We have developed over the last pieces different sets of compositional rules that allow the performer some freedom of choice and interpretation within the movement material.” In many ways, she combines the old with the modern. “I am what you might call a New Traditional Choreographer,” she affirms.

This way of working offers freedom and discipline to the company. Stammer productions are known for their intellectually rigorous take on dance, yet Sadler does not agree that this makes her work inaccessible.

“I think dance and performance is for everyone. That doesn’t mean everyone is interested in it or that dance should try to compete with mainstream entertainment.” Her knowledge of academic theory does lead Sadler to an abstract and dry intellectualism. “Actually I think the whole notion that audiences need everything spelled out an insult to their intelligence and will lead to an eventual death of the art form.”

Her own experience of working with young people suggested that contemporary need not be obscure. “Last year and this year I initiated a children’s project in Glasgow schools bringing excerpts of my work to those who normally would have no chance to access or know about it. We had an overwhelming response which proves to me that maybe we just have to work harder so that dance and performance can be appreciated as part of cultural knowledge. There is very little in general written about dance unlike music or visual art so its a continual process to raise the profile and understanding of what dance is and how one might appreciate it.”

For Musical the humour “is part of the process of democratising access to the work.” She admits to some frustration at the continued marginalisation of dance. “I am totally bored of people talking about how dance is inaccessible and begin to ask myself if those who people who keep talking about it in that way do not understand it or even like it.”

Indeed, responses from audience members suggest that Stammer have been reaching out to new fans. “After our last show in Tramway I received an e-mail from an audience member who never goes to see dance talking about his impressions of the work. In Vienna, a woman told me after our show how she came all the way from Paris for the festival and was really happy she made the journey.” This communication beyond the dance world informs Sadler’s attitude. “As the famous American choreographer Martha Graham once said you always talk to at least one audience member and I believe her.”

Comments