Alex Boyd is a photographer who specialises in early photographic methods. This is were he creates…

Alex Boyd with his portable camera, Downpatrick Head, Ireland

For several years now I’ve been working as a photographer specialising in historic processes such as wet-plate collodion. This is one of the earliest ways of making images and was first invented in 1851 by Frederick Scott Archer.

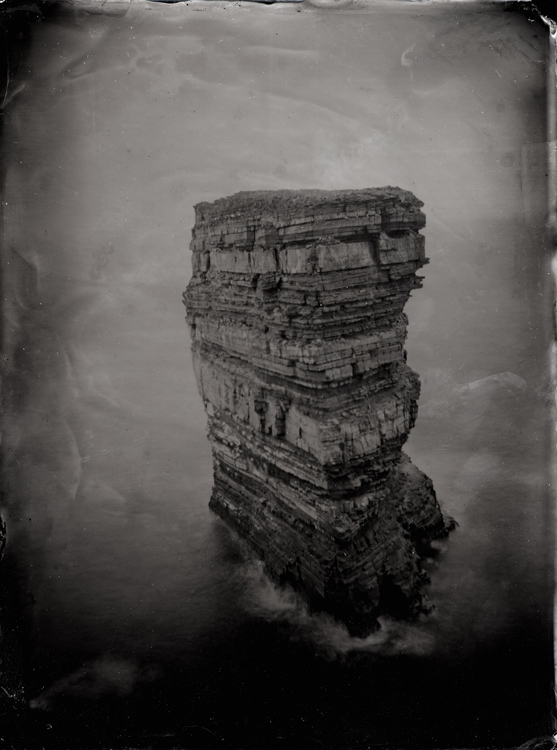

Den Bruiste Sea Stack, County Mayo, Ireland

This process has the slight downfall that it requires you take your studio with you, with enough chemicals, supplies, water and materials to make images wherever you are working.

It currently takes a car to move my studio from one location to another, with little room left once the camera and my darkbox are packed alongside me. If I’m working inside, in a dedicated studio space, or an improvised one such as the vaults of Stirling Castle, then making images is fairly straightforward, as long as there is an ample supply of light and water, and the chemicals such as silver nitrate are behaving themselves.

Inside the darkbox, portrait on tintype

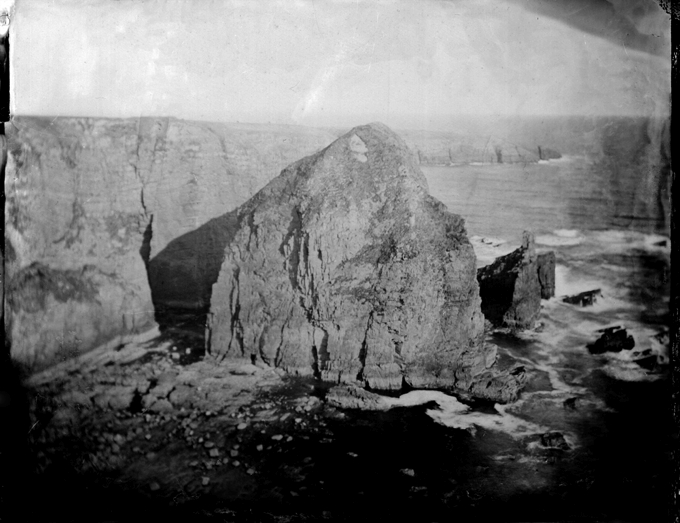

Working outside in the landscape however brings a whole new set of challenges, difficulties and frustrations, however it is probably where I most enjoy working with this process. Setting up my portable darkroom, in effect a large wooden box in which I can work in the field, I need to contend with high winds, rain, snow and intense heat and in the case of a residency on the Atlantic coast of Ireland I undertook earlier this year, all of these within a matter of hours. Difficult locations also mean that you have to drag all the gear to where you want to make images, sometimes a back-breaking and laborious task.

Alex’s studio, WW2 bunker, Downpatrick Head, County Mayo, Ireland

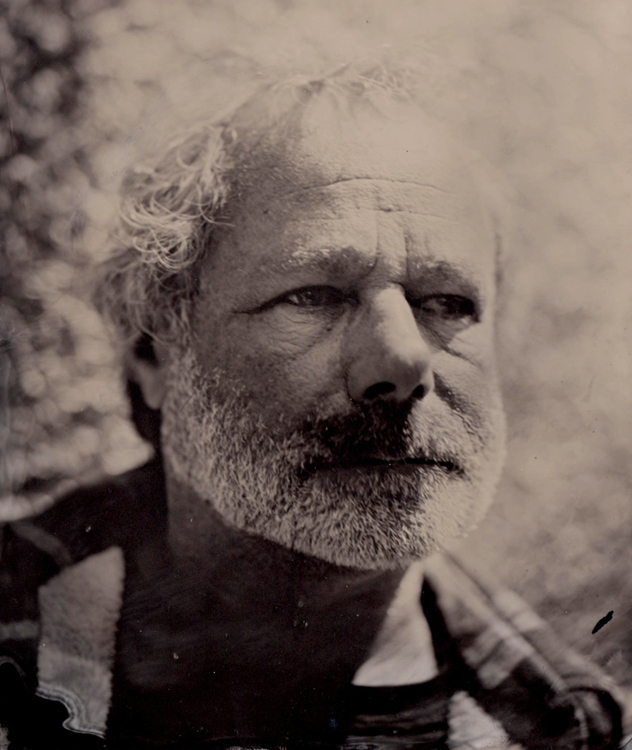

Scottish artist Hugh Loney

To date I’ve worked across Ireland, Scotland and England with my darkbox, everywhere from Rannoch Moor up in the Highlands, to the ruins of several Second World War clifftop bunkers in County Mayo in Ireland. Working in this way allows me to completely immerse myself in each location, due to the slow and methodical approach to image making, with each plate taking 15 minutes from the moment I pour collodion on the glass, to the final development using potassium cyanide.

Darkbox, camera and chemicals in studio

I’ve been asked many times why I persevere with collodion photography, especially given the difficulties in producing images using chemicals and the need to bring so much equipment with me. The answer is a straightforward one – it perfectly complements the way I make images. I found that with film and digital my approach was slowing down and becoming more contemplative, and that I was investing more time into each individual shot. This of course does change with the subject, however for landscapes I would say that my pace at the moment is fairly glacial.

Cashlanicrobin Rock, County Mayo, Ireland

The approach also produces distinct images. Aside from collodion’s unique aesthetic, each image is a moment in time recorded on glass, not just the scene before me, but every flaw and imperfection which goes into making that image. This can range from chemicals producing chaotic and unexpected results, to blades of grass from the side of Loch N-achlaise or midges from Glen Etive trapped forever in the collodion like amber. The corner of every image also contains my fingerprint from where I held it during its creation, a marker which signifies that I was there.

The Old Tree Graveyard, Ballycastle, Ireland

Alex Boyd is currently the RSA Artist in Residence at Sabhal Mòr Ostaig in Skye.

Find out more:

Website | Blog | Flickr |Facebook | Twitter

//////

‘Where I Make’ invites readers behind the scenes of artists from many disciplines to share photographs and a little insight about where they create their masterpieces. See more from the series here.

Comments