On Julie Roberts, Child.

Talbot Rice Gallery, Until September 25th.

‘There is a sweetness about these paintings that can immediately make you think that they are just sentimental, historicised images of children from the 1950s- with their buckled shoes and their party dresses- but you need to look again.’ Pat Fisher, Exhibition curator.

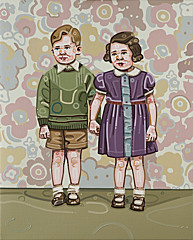

Staying Together, 2010

Seventeen children gaze out from a large bank of pencil drawings- some stare absently into the distance, others squint oddly, whilst some confidently look the viewer straight in the eye. They resemble normal portraits of happy children, posing for their annual school mugshot- but something here is not quite right. Julie Roberts’ works have a disconcerting quality- an awkward dual impression of contemporaneity and out-of-time-ness that creates a sense of the uncanny that is not instantly possible to equate or resolve.

There are no adults here. One young girl prays alone at the edge of her bed, another carries a bouquet of flowers as an unexplained offering, three adolescent boys tuck-in to an anonymously prepared meal- all sharing a contented commitment to their respective mundane pursuits. There are none of the traditional vibrant primary colours of childhood here- instead the work is realised in a stern, muddy palette that Catriona Black describes as being ‘evocative of urine, vomit, and nicotine stained minor’s clubs.’ However, in spite of (or perhaps as a result of) the austerity of their surroundings, there is no sense of despair or longing- each child exhibits a level of mature self-sufficiency that is at once as admirable as it is disquieting.

Will Bradley notes that Roberts ‘builds up meaning in a network or relationships between paintings that extends across her whole body of work, apparently innocent images taking on new overtones as they echo more sinister set-ups’. A consideration of the artists’ early life and previous works is vital in fully appreciating the paintings in Child. Having spent periods of her own childhood in care- Roberts brings an autobiographical implication to the work and, tracing back her previous artistic exploration of institutional structures of power, renderings of medical equipment and apparatus, as well as her depictions of various corpses and cadavers- the works adopt a richer, foreboding aura that resonates around the yawning main gallery space.

There was an initial proposal to adopt Feral Child as title for the whole exhibition- an idea that was rejected for being too emotive and limiting, in favour of the more arresting and ambiguous nature of the shortened Child. Whilst ‘feral’ evokes immediate wild and animalistic connotation, it also defines an organism that leaves or escapes from domesticity to return to a more natural, intrinsic condition. For Roberts’ children, who have been displaced from their familial environment, be it through evacuation, being orphaned and/or taken into care- the description rings with a poignant aptness. (It is interesting also to note that the word feral has a second, unrelated meaning from the Latin ‘feralis’ meaning ‘belonging to the dead’).

Advocation of childhood independence was among the main principles taught by Italian doctor Maria Montessori in her pioneering child education work in the early 19th century. She promoted a hands-off approach to teaching, allowing for the child’s inherent natural directives to guide their development. Roberts overtly introduces the method in Refugees at the Montessori School, depicting children within an environment designed for this development to flourish; tables and chairs are of a proportionate size and pictures and tools are hung at an appropriate level, allowing the children to function and learn without adult interference. In this instance however, they have been disturbed- all activity is paused, replaced with a collective outward gaze towards the intruding spectator. Their stares filled with puzzlement and annoyance at the unwelcome interruption.

Roberts works from photographs, both found and from her personal family archive, a fact that accounts for the uneasy composition of some of the work here. In Human Material a young boy sits in a stark bathtub- he has no toys, no bubbles, no potential for fun. Curator Pat Fisher invites the viewer to ‘consider the position of things like the soap. Now that is obviously not within the child’s reach’. Reasoning that ‘it could only be me who could reach that soap and wash him.’ Since the original photographs where presumably taken by an adult, this is the perspective offered to the viewer- they are unwittingly implicated as the absent grown-up in the scenario, cast frustratingly in an unfulfillable position of responsibility.

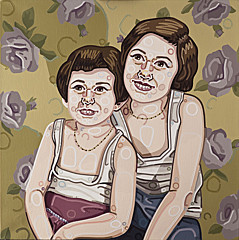

Anne and Margot Frank, 2010

A strong notion of kinship is fostered in Child. The work Staying Together depicts a brother and sister hand-in-hand, strong in the face of their shared isolation and many of the ‘feral children’ exist in bonded pairs- siblings in matching jumpers. Exemplification comes in the painted portrayal of Anne and Margot Frank. Anne (who herself attended a Montessori school) is generally recalled as a lone-figure, but here she is found alongside her elder sister Margot- bound together by a striking facial likeness, matching tunics and grins. The girls, iconic figures of childhood resilience in the face of extreme adversity, remained together through their years of hiding and incarceration before they both finally succumbed to illness within days of one another. Knowledge of the tragic future awaiting Anne and Margot haunts not only their own carefree faces, but extends to the other children in the room, prompting bleak contemplation of what similar fate may lie ahead of them.

Upstairs in a cabinet of curiosities are old photographs, swatches of aged patterned fabrics and artists’ sketchbooks- as a ‘good housewife’ from the 1950s beams beside her sink in vivid retrocolour, Roberts’ pencil rendering of her stands alongside like an eerie, pallid twin. This offered glimpse into Roberts creative process goes some way to aide the understanding of the uncanny tension found in the final works. This collated material, themselves already depictions of the real, are then subjected to further transition by Roberts through her re-drawing and interpreting them into her stylized paintings. Each stage of the process, from research and collection to the development and realization of the finished works, are directly mediated by the artist, thus being subtly yet indelibly impregnated with traces of her hand and private experience. The results are images that whilst holding a familiar sense of the real, remain inexplicably off-kilter.

Other works on the upper floor reflect Roberts’ exploration of traditional gender roles- namely within the family institution; daughters act as domestic apprentices to their watchful mothers, folding sheets on wash day and peeling vegetables- at the far end an infant girl tenderly cradles her doll, preparing to train the next generation and perpetuate the established domestic cycle.

The final child to meet is Edna (British Evacuee). Orphaned in the galleries round-room, she is surrounded by an unwieldy floral wall-painting that feels somewhat incongruous to the archaic and autonomous worlds captured elsewhere. Regardless, Edna boasts a now familiar, stoically confident complexion- hat donned and duffle coat fastened to the neck- fully prepared for whatever she is set to face.

Edna (British Evacuee), 2010

Comments