Graham Fagen appears admirably calm and collected as he presents the work he will be showing at the 56th Venice Biennale to a room full of journalists. He jokes about early aspirations of playing for Scotland on the football field and it feels fitting that he will have the chance to represent his country within the arts world. Curated by Hospitalfield in Arbroath, Scotland, Fagen’s exhibition will be held in the Palazzo Fontana, a new exhibition space for Scotland in Venice. He will be exhibiting new work across a series of rooms including a bronze rope/tree sculpture, an audio piece, a selection of drawings and a multi-channel AV installation.

One of the pieces to be shown explores a poem by Robert Burns. The Slave’s Lament is a recorded musical performance by the Scottish Ensemble. Graham worked with composer Sally Beamish, musician Ghetto Priest and music producer Adrian Sherwood to include references to reggae, folk songs and classical music in this ambitious piece. It encompasses a 5 channel AV installation whereby four of the channels will be linked to four screens. Each screen will show a video of the individual musician playing the piece and as the viewer approaches any one particular screen, that instrument will be singled out to be heard more clearly as the visitor gets nearer.

Production image, (L-R: Diane Clark and Graham Fagen), Graham Fagen, The Slave’s Lament, 2015. Photo: Holger Mohaupt.

Production image, (L-R: Graham Fagen, Sally Beamish, Ghetto Priest and Jonathan Morton), Graham Fagen, The Slave’s Lament, 2015. Photo: Holger Mohaupt.

What do you ask one of the most influential artists working in Scotland today? We had quite a few things to put to Graham, but decided to open up this opportunity to all of you in our Ask Graham feature and we’re glad we did! Below are Graham’s responses.

Q: Central Station

The exhibition at Venice has been curated by Hospitalfield Arts. How much input have they had into your work?

They’re helping me achieve the work that I want to make. I suppose their input comes in the shape and form of help and support. I’m working with Jane who is the Producer of the project and she’s working with Hospitalfield to help me make what I’m trying to make.

As one of the largest and most prestigious visual arts exhibition in the world, how have you dealt with the pressure of creating work for the Venice Biennale?

As an artist you deal with your own pressure; the pressure’s always from yourself. In my experience, it doesn’t really matter who you’re making the exhibition for. You’re working to the pressure of yourself. You want to do the best job that you can. It doesn’t matter if it’s for the gallery at the flat of one of your friends or whether it’s at the Venice Biennale. That pressure that you get is from yourself about doing the best that you can is the most important pressure to pay attention to.

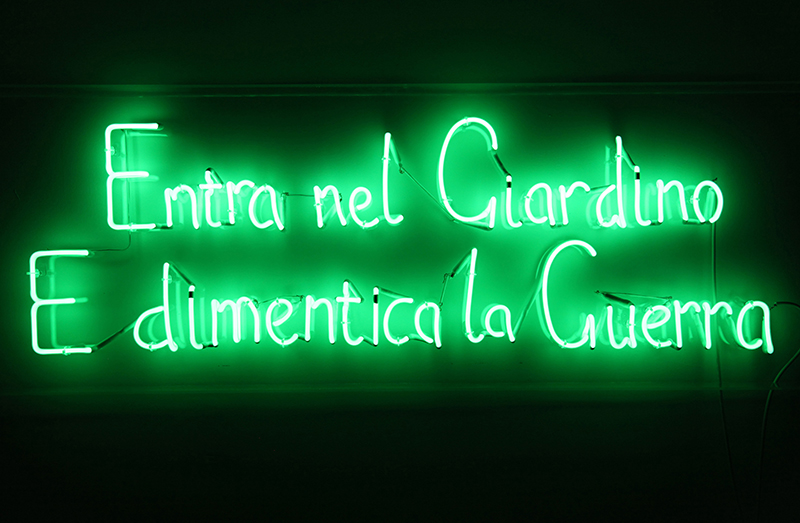

Graham Fagen, Guerro/Giardino, 2015, neon and acrylic, 180 x 60 x 12cm. Photo: Graham Fagen.

Q: artist Liz West

What does a day in your life look like?

A mess! [Laughs] I suppose it depends on what job I’m working on. We’re in Glasgow Sculpture Studios just now so I’ve been spending some time in the studio. Some days I’m down in the workshops. I’ve got a studio at home so some days I’m working there. Sometimes I’m at Powder Hall Bronze in Edinburgh. Some days I’m editing with the editor I work with. Sometimes I’m in London, sometimes I’m travelling. I’ve got an opening in Berlin in two weeks time, so it’s lots of different things. There’s no typical day. There’s days where you’re having to do different jobs; you’re doing the job that needs to be done on that particular day.

What made you decide to become an artist?

That’s a good question. I don’t think it’s something that I’ve consciously decided to do. It’s only fairly recently when somebody’s asked me what I do that I’ve had the confidence to say I’m an artist. I did an undergrad in sculpture in Glasgow and I was able to make things that people were interested in, but I didn’t know at that time why they should be interested in what I was making. For me there was something missing. I did a masters in architecture and I read a book by Irwin Pernovsky called Scholastic Philosophy in Gothic Architecture. That book did a really simple thing of connecting a philosophy with form, also connecting form with philosophy. That book was a revelation for me. It gave me the thing that was missing. It gave me the reason why I could make something and why people should take it seriously. I suppose that’s what I’ve been trying to do as an artist.

Does teaching interrupt your ability to practice?

I’ve been lucky in that it hasn’t. I don’t teach full time. I’m on a fractional contract and I get a lot of support from Duncan of Jordanstone to do my own work. A percentage of my contract is for research and a percentage is for teaching. There’s times like doing this project and times when I’ve been doing projects in the States and I’ve gone and lived there. Duncan of Jordanstone have always been very supportive and allowed me that time to do the work. On the contrary, rather than the teaching getting in the way, the teaching has actually helped to support and enable me to do the things that I do. Also, at times you can get too close to your work and on the days you’re teaching, it’s a privilege to change the head for that day. And it’s a privilege to hear other people’s thoughts and ideas and to share conversation about them. I think that experience keeps my own art practice grounded and keeps me thinking about it. It keeps it alive.

Q: artist Lesley Finlayson

If you could collaborate with any artist who would it be?

I would make a fantastic film with John Waters.

Q: artist & curator Alex Hetherington

I am very interested in a line that you draw between visual art and theatre specifically in the work you have done with Graham Eatough in the pieces ‘Killing Time‘ and the ‘Making of Us‘. Can you describe this process of making live work that has its roots in visual in the contexts of theatre and how will this subject impact on the work you will be making for Venice?

The things that I like about working in a collaborative aspect, not just with theatre directors but with Sally Beamish our composer or Adrian Sherwood our music producer is the fact that I don’t really know what the lines or the boundaries are. Maybe what it is is working between lines and boundaries of disciplines or things that are supposed to be disciplines to break that strict concept of disciplines. I think that’s what I like about it – I guess in essence I’m just doing what I want to do and not letting boundaries or disciplines be guides or hindrances for the way that it should work. I think it’s great and fine that people should go to an art gallery and hear music or see a bit of live acting.

I am also particularly interested in the poetic and the poetry that appear in your work often, roses, journeys, songs, that have a feminine quality. How do these work with or against the more masculine, tragic, abject or brutal passages?

When I was a war artist for Kosovo I came back with a few thoughts and one of the strongest was that women should rule the world.

For more information on Graham’s work, see his GENERATION exhibition review by Rachel Boyd on Central Station here.

More: Website | Facebook | Twitter

//////

Want to read more Q&As with creatives? Find them here.

Comments