Central Station brings you a special preview of Duncan of Jordanstone’s Degree Show 2013 which runs from 18 – 26 May in Dundee. It is written by Kevin Smith who is studying the MFA in Art & Humanities course at DJCAD.

There’s been a strange air surrounding Duncan of Jordanstone’s ‘Art & Media’ class this year. Talk to anyone familiar with the group and, almost without exception, they would nod enthusiastically and say something like ‘It’s a great year…. They’re a talented bunch’. It was with high expectations, then, that I began wandering through the various gallery spaces, hopeful that this year’s Degree Show would live up to that remarkable uniformity of reputation.

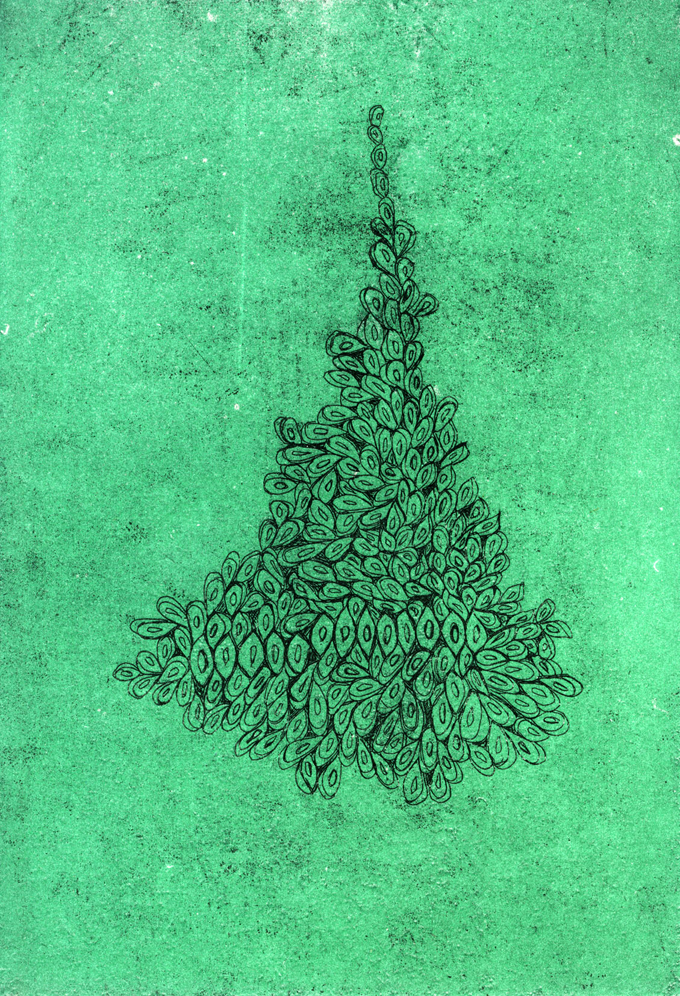

What quickly becomes apparent is that this year is full of ‘makers’- students far more fascinated by materiality and experimentation than high concepts. Jonny Lyons has made a series of ‘functioning sculptures’ (a rifle, a telescope and a rocket launcher) surrounded by photographs which capture the moment of their function. The result is both engaging and melancholic, harking back to the sort of well-spent childhood when just building and doing were justifiable ends in themselves.

Nearby are two sculptors who let the material do the talking. Sam Baxter collects and reassembles South African ‘Protea’ flowers; the result is gentle and quite beautiful. Considerably less selective in his use of materials is Liam Birnie (I spotted resin, gold leaf, acrylic, plywood, glass and wax), but the materials are treated with a similar care and sensitivity, and side-by-side these shows work well.

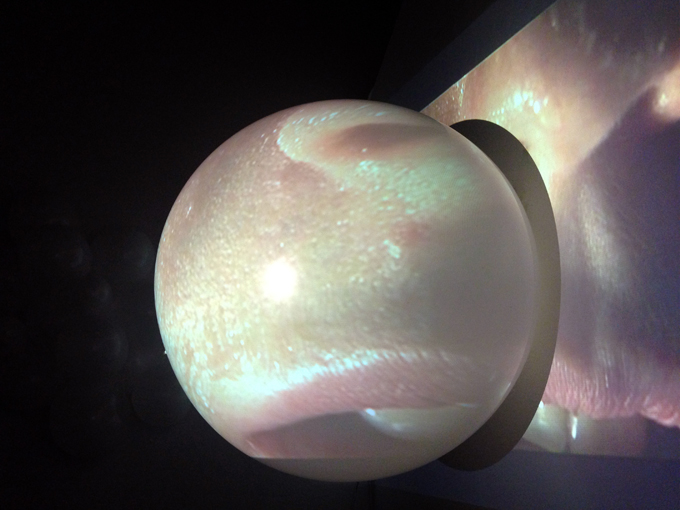

Claire Morrison’s work addresses themes of panic. Her installation of an eye projected onto giant white balloons, held motionless by their own static charge, is an effectively uneasy space – as the room breathed deeply so did I. Liam Dunn’s work evokes another sort of fear: the fear of passing time. His boxes of art-debris address that central art school anxiety: all this creative energy expended…. Now what?

If the post-Art School world seems a frightening one, it makes sense to go about creating your own. In a relatively small space Mary-Beth Quigley, Lindsay Stephen and Rhory Gardiner have built three very different, but no less immersive, environments. Lindsay’s camouflage installation interestingly explores the notion of the soldier as an individual. The other two spaces are beyond quick summary, but suffice to say that Mary-Beth’s show has giant animals (although her giraffe is probably slightly smaller than a real one), while Rhory’s took me back to grander days spent watching ‘Jungle Run’ (the magnum opus of 21st century children’s TV).

Perhaps the maddest show of all is Daniel Bruton’s installation, replete with painted rocks, cardboard armour and a shopping trolley. In a show conspicuous for its craftsmanship, Daniel’s constructions are daft and entertaining (the video of him perpetually rowing his trolley towards a ramp is as frustrating as it is amusing).

There is a sense of humour too about Calum and Fraser Brownlee’s work. Knife handles have been replaced with butt-plugs, dildos turned into nunchucks, and a wax pig’s head skewered by a spear. In a more frenzied space such provocations might appear contrary, but the show is considered, perhaps even perversely serene; it’s quite difficult to put into words, but what I can say for sure is that a broadsword’s handle looks surprisingly appetising when it’s deep-fried.

Upstairs, Matthew Wilson’s vivid prints transform simple scenes and objects into things of real beauty, and, although his graphic approach is familiar, the assembly of his show is pitch perfect.

In one of the quietest settings, Lewis Matheson presents a series of black and white photographs that freeze the subtle undulations and transience of flowing water. Nearby a small book of poems sits on a lectern facing out over the Tay and beyond. This is the best view in the building and Lewis’ work fits it perfectly.

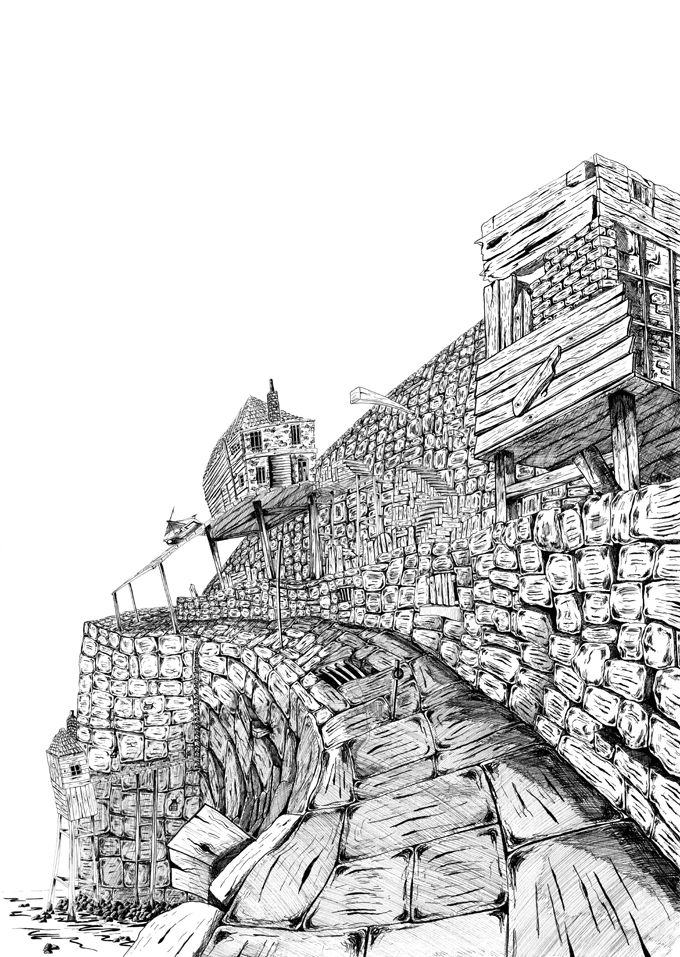

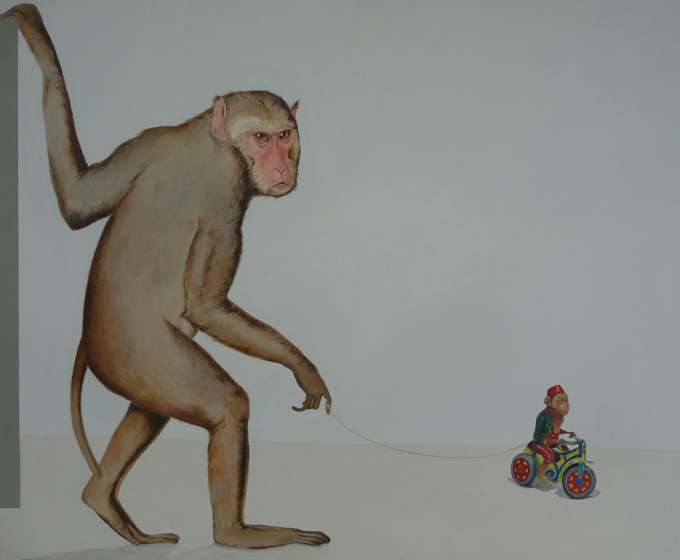

In the large gallery space downstairs, John Kelly has made great use of an awkward space; his drawings and models of precariously stilted dwellings are superb. Allan Davies is a tactile and skilled painter; his painting ‘Pte Forbes and Two Chameleons’ is an understated delight.

In Time Based Art (make sure you go) Calum Crotch has created a sort of neon workshop, in which his giant origami constructions and interactive installations illuminate and burst with energy. Jonathan Douglas’ uniquely impressive and honest work tackles alcoholism and the modern conflict of giving over to a ‘power greater than oneself’. The work is striking because, considering its themes, it is neither disdainful nor message driven. Rather, it quietly evokes the pains, struggles and redemptions of modern life.

It is worth noting how little ‘message art’ (the type of overly-clever, overly-didactic work which often populates student exhibitions) is on show here. Instead, when the statements come, they are serious, restrained and thoughtful. Chloe Kelman’s show focuses on the erosion of Romany Gypsy culture. Her low-lit space, filled with little glowing caravans and punctuated by the light and crackle of fire, is warm, inviting, and poignant. Shazia Ahmed is no less politically engaged; her shredded currency and flags made from supermarket bags cleverly deconstruct familiar consumer codes. Shazia describes herself as ‘a satirist’, but it’s all much too nuanced for that.

The next room I enter is presided over by a giant amorphous figure that seems to stare at me for the duration of my stay (though it has no eyes). This is Callum Reid’s sculpture, ‘Morbid’ – it is a viscerally effective manifestation of the modern sicknesses he wishes to evoke. (I am yet to discover how significantly it will haunt my dreams).

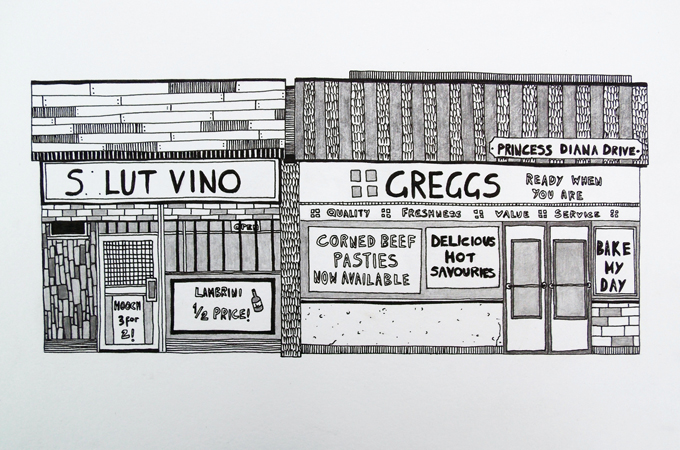

The last room I visit contains two very distinct narrative-driven shows. Eilidh O’Fee’s ‘The Town’, is a clever composite of several towns and cities exposing the nightmarish uniformity, and peculiar charm, of modern town planning. Through a series of meticulously crafted sculptures, Rosheen Murray gives new life to old stories. ‘My What Long Hair You Have’ for example- a woven basket which becomes a plaited ponytail- instantly conjures a familiar fable while standing as an arresting artwork in its own right.

This of course, only begins to scratch the surface of what’s on show here. Unmentioned are clever experiments, frenzied collaborations, examinations of sexual identity and vast romantic paintings, all too much to discuss even in a long-winded review such as this. From now on, if anyone asks, I’ll probably just nod enthusiastically and repeat what, in my mind, has become the show’s tagline ‘It’s a great show…. They’re a talented bunch.’

See the Duncan of Jordanstone Degree Show 2013 from 18 – 26 May 2013, Dundee

Comments